Abalone, squid and sea urchins are not my everyday seafood, but that’s what I was recently having for lunch in Busan, South Korea’s largest port city. Even more impressively, my lunch was not caught by a fishing boat, but by an 82-year-old Korean grandmother who harvested it from the deep ocean with no diving equipment whatsoever.

Lean and agile, Yun Yeun Oak is a haenyeo, Korean for “sea woman,” who can hold her breath for two to three minutes at a time while diving up to the depth of 60 feet, equipped only with a mask and fins.

Credit: 2024 Dennis Cieri

“I dove my whole life,” Yun Yeun Oak told me, adding that this breath-holding technique called sumbisori has been passed from mother to daughter for generations. I could not help but marvel that this ancient profession still exists in Busan’s 21st century metropolis where massive fishing boats offload tons of catch daily.

South Korea, as I learned on my nine-day tour with Intrepid Travel, is a country of curious contrasts.

In Seoul, centuries-old palaces nestled in between skyscrapers and traditional markets elbowed shopping malls. Pharmacies sold both herbal concoctions and modern meds. Young Koreans donned colorful traditional Hanbok dresses to visit temples and palaces, and proudly posted their selfies on Instagram and TikTok.

“They love being old-fashioned and modern at the same time,” explained Michelle Hong, my Intrepid tour guide.

RELATED: What to Expect From a South Korea Temple Stay — And How to Book One

South Korea blends ancient and modern with grace few countries are capable of. Here are several places to visit with Intrepid for a fully immersive South Korea cultural experience.

Andong Hahoe Folk Village

A 600-year-old community and a UNESCO World Heritage Site, the village was built against the mountainous backdrop and encircled by the river — according to the rules of Feng Shui, a holistic practice that uses nature’s energy to harmonize humans with their environment.

Credit: 2024 Dennis Cieri

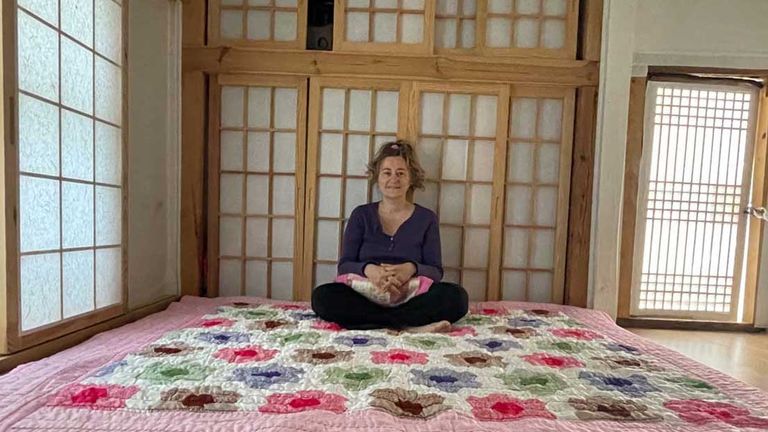

Here residents still live in traditional Hanok houses with gabled roofs and centuries-old heating systems that distribute warm air from kitchen fireplaces to rooms via underground stone channels called ondol. As we retired for the night in one of the Hanok houses, I worried about being cold or uncomfortable sleeping on a floor mat instead of a bed.

RELATED: Review: Indigenous Experiences in Costa Rica With Intrepid Travel

Whether it was Feng Shui or the warmth that radiated from the floor, I slept soundly through the night and woke up fresher than ever, despite the jetlag. In the morning, after I savored rice porridge with homemade kimchi, my hosts Ryu Ji Han and Moon Do Won showed me their ondol and vegetable garden.

“We grow all our cabbage for kimchi ourselves, like our ancestors did,” they said proudly.

Intrepid guide Michelle Hong recommends the village’s traditional masked dance performance, which usually starts at 2 p.m.

Abai Village

Originally a temporary settlement for about 7,000 North Korean refugees who escaped from Pyongyang during the 1950s Korean War, the Abai Village has evolved into a cultural center in its own right.

Credit: 2024 Dennis Cieri

In Korean, “abai” means an aged person, and many refugees have settled there, raising their families and even grandchildren. While I practiced dumpling-making with Kim Yong Joe, also in her 80s, she told how her family ran away from North Korea, and how 70 years later, she still misses her hometown. She hopes that one day the two Koreas will unite, and she’ll go back home.

“I’ll finally be able to see the rest of my family again,” she said.

RELATED: A Guide to Family Travel in Seoul, South Korea

That persistence is part of Korean character — that’s how the entire country is able to preserve their cultural heritage as time passes.

Busan Yeongdo Haenyeo Culture Exhibition Hall & Restaurant

Nestling on the rocks at the ocean’s edge, the culture center houses a restaurant where haenyeos serve their daily catch and an upstairs exhibition that shares their history. The ancient haenyeo culture originated on Jeju Island, from where it spread to other parts of the country.

“I grew up on Jeju and learned sumbisori from my mother,” Yun Yeun Oak told me. “I’m still diving, several times a week, with other haenyeos. We get up very early, at dawn, and go off to sea.”

Most of Yun Yeun Oak’s diving mates are in their 70s and older, but they aren’t passing their skills to their daughters anymore.

“This profession is too dangerous, and it doesn’t make a good living today,” she said. “We’re the last haenyeos.”

The sumbisori technique will die with them, and their profession is now inscribed by UNESCO as intangible cultural heritage. If you want to savor seafood caught by the few remaining sea women, don’t wait too long. Visit now, while they’re still diving.